Down there. Fanny. Lady parts. Fufu. Vajayjay. We’ll use almost any euphemism to avoid saying the word ‘vagina’, but that needs to change. Treating vagina as a dirty word only feeds the shame so many people feel about their bodies – and that shame has real world consequences. UK gynae cancer charity, the Eve Appeal, found that a third of 16–35 year olds women admitted they had avoided going to their doctor about their vagina or vulva due to embarrassment.

Imagine going to the doctor and telling them that you have a pain in your vagina. The doctor will do an internal examination, but what if you actually meant your vulva? Florence Schechter, the founder and director of the Vagina Museum, says that these kinds of unnecessary invasive procedures are worryingly common.

Doctors often won’t stop to check whether people know and are using the anatomically accurate words to talk about their genitals. Schechter says that people struggling to describe where their pain is leads to misdiagnoses, especially with pain disorders like vulvodynia and vaginismus.

Ovarian Cancer Action found that 66% of women aged 14–24 in the UK say they’d be embarrassed to say the words ‘vagina’ or ‘vulva’. Meanwhile the Eve Appeal found when asked to that correctly identify the five areas that can be affected by gynaecological cancer (the womb, cervix, ovaries, vagina and vulva) on a simple diagram, only half of participants aged 26-35 were able to label the vagina accurately.

You need information to make informed decision. Schechter explains that when “people don’t know about their bodies, they can’t make informed decisions about their health, keeping themselves safe, getting pregnant, or family planning.”

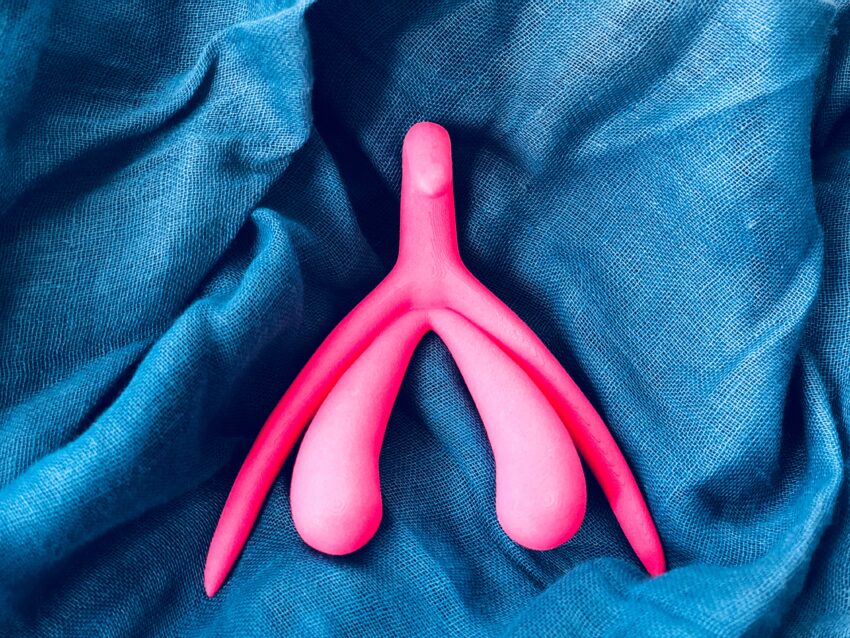

Many people simply don’t have access to that information. When Lulu, who is 29 years old, discovered small bumps on her vulva, she worried that she had an infection. An emergency Saturday trip to their local sexual health clinic revealed that they were Fordyce spots. In her book, V: an empowering celebration of the vulva and vagina, Schechter explains that Fordyce spots are “light in colour, totally painless and about 1–3 mm in width.”

Fordyce spots are completely normal, but Lulu had never heard of them. Accurate information about how their vulva might look would have reduced her anxiety: “I definitely wish sex education [in school] had mentioned them, and just generally we’d seen more examples of what genitals can look like.”

Rather than normalising what genitals can look like, it’s more common for people to have been shown graphic images of genitals with STI symptoms during sex ed classes. (Even though many people who have STIs do not notice symptoms – for example, around 75% of women and 50% of men with chlamydia are asymptomatic.)

These images are not only unrepresentative of what STIs look like, but research has also shown that using scare tactics or “fear appeals” to dissuade young people from having unprotected sex is ineffective. Justin Hancock, a relationships and sexuality educator who runs BISH, argues that showing students images of genitals with symptoms is counterproductive: “Sexual health education, which seeks to ‘disgust and dismay’ is going to create more stigma around STIs and thus around accessing treatment. Delaying treatment, or avoiding treatment, increases the risk of transmission and increases the risk of long-term health effects.”

In the absence comprehensive sex education in schools, organisations like Vagina Museum are stepping in to teach people about their own bodies. Schechter says: “We get loads of feedback from people who are like, ‘I didn’t know this about my body.’ ‘You’ve changed my life.’ ‘I brought my boyfriend here and he learned loads.’ Or ‘I wish I had this when I was a kid.’”

Despite concerns around whether the sex education young people are receiving in school isn’t “age appropriate”, giving young people information about their own bodies can help protect them from abuse. Schechter says explains that “if young people don’t know the words for their body parts and they’re being abused, it can be harder for them to explain what is happening to them.” Without the right language to talk about it, they can’t get the help they need.

Being able to say ‘vagina’ loudly and proudly isn’t a magic wand. It’s not going to take away people’s shame overnight or leave us equipped to talk about our bodies. But it’s an important first step in having the tools to advocate for ourselves in medical settings, so say it with me: va-gi-na. Vagina.

Further reading on vaginas and dismantling shame:

V: an empowering celebration of the vulva and the vagina by Florence Schechter.

Sex Ed: A Guide for Adults by Ruby Rare.